The Returns to Volatility

How do you live your best life? (for all you career maximalists out there)

Cap your existential downside risk, pursue max volatility, repeat.

This is a companion to The Perniciousness of Infinite Loss. They’re a finite set (order doesn’t matter). Read both. Or neither. Doesn’t matter. We’re just glad you’re here!

An option in financial terms is typically a security that gives you the right, but not the obligation to do something.

It’s basically a bus ticket.

No one is making you get on the bus, but you can if you want to since you already paid for it.

An option is a useful tool (not just for Big Bus execs) and the idea unlocks a lot of fun math.

For our purposes, we care about call options. Well. Technically American call options.

Naming in finance is dumb tbh.

An American call option gives you the right to buy a stock or some other financial instrument at a preset price for some period of time until the option expires (but you don’t have to).

Why would you pay for this when you could just…buy the stock you like?

Well, if the stock price goes up during your call option’s period then you can exercise the call and make some $$$.

By exercising the option you can purchase the stock (or whatever) at the earlier, cheaper price and now you can immediately sell the stock at the current, higher price and lock in some amount of profit. You pay for this option upfront with a fee, but if the stock goes up enough it will cover your initial fee and be financially worth the effort and initial cost.

Let’s look at this toy example.

Let Stock X be worth $10 today. At our imaginary brokerage, you could buy 1 share of Stock X for $10 right now or you can pay $1 to purchase a call option on Stock X at the current price.

Let’s grab the call option so this is our net position:

Spent $1 | Gained 1 $10 Call option on Stock X (currently worth at $10 a share)

So in a scenario where Stock X goes to $20 a share tomorrow we can exercise our call option at $10, which importantly means spending $10 to buy a share of Stock X, and then sell our newly purchased share of Stock X for $20.

This gives us a gain of $20 minus $10 cost minus the $1 fee so overall $9 profit without assuming any price risk. Not bad.

Side note: if you’re in tech and are ever granted equity compensation, look at the fine print on the tax consequences of exercising/vesting because it can get pretty complicated. I’ve met some smart people who…have underexplored this issue.

Anyway, astute mathematicians might notice that if we had just bought one share of Stock X at the start we would’ve earn $10 of profit (bought at $10, held until $20, and then sold), which is true, but we also would have internalized the price risk in the downside scenario.

AKA if Stock X had gone bankrupt the next day after our purchase, we would’ve lost our $10. With a call option, we pay $1 to offload that downside risk to some other party.

Not our problem! We just work here.

If you think this stuff is neat, wait til you hear about put options! A Put option does the same except for locking in a selling price for a stock or security. This is useful if you like shouting at CEO’s for doing bad things and making money off of that. There’s a ton of other things that we could go into and options can get pretty weird, but we’ve explored most of what we need to explore here.

Who tf cares? I want self-actualization!

Now an interesting question.

Markets (abstractly and concretely) are basically just everyone arguing with each other over prices with the goal to eventually minimize waste/maximize utility in an economy. Finding the right price is important to all parties involved and, in an environment like that, it becomes pretty clear that options are a super weird thing to price.

How do you estimate the value of a claim to an action in the future?

How does this price change over time as new information enters the market?

Are calls worth more than puts? Why? So many interesting questions.

If you’re boring it’s probably something like an options price equal the estimated value of future stream of cash flows less fees spent already less some uncertainty factor, but we can do better than that.

You can look at the many many many many academic papers and wow at the Nobel prizes some nerds won. We won’t go into the depths of that today (summary for you mathematicians out there), and even we did there’s honestly like some very real probability that we can’t ever price options accurately because even our best models have to meet these arbitrary conditions.

This whole dumb setup leads some smart people to say silly things like this:

but what’s really weird and unintuitive (even beyond the fact that billions of dollars are made and lost on what are essentially quants squinting at their models and shrugging and saying eh that’s probably good) about options is this humdinger.

The value of an option goes up with volatility of the underlying asset.

How nuts is that?

The less predictable the future price of an option is, the more we should rationally be willing to pay for it.

Don’t believe me? Go here and play with the volatility slider. I mean, I didn’t check his math, but let’s be real - neither will you.

So let’s just agree to pretend we did our homework and keep rolling.

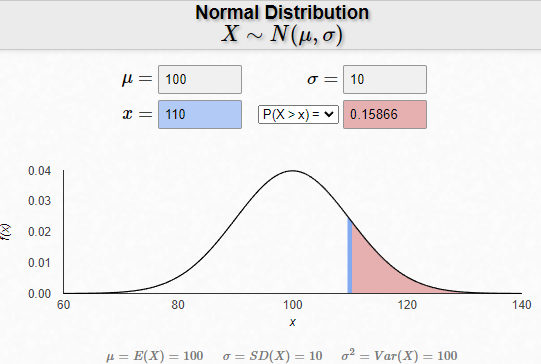

Visualized, this is volatility.

Let’s say we own a call option that we paid $10 for on a stock with a price of $100 right now. This means the stock needs to hit a price of $110 for us to turn a profit on exercising this option.

Now let’s assume a normal distribution of prices for that stock (we should technically use a lognormal but this calculator was prettier so go with it) and the stock also has a standard deviation of $10 (that’s a rough measure of the distance from the current price we can expect the price to trend towards in a large of number of repeated trials). This means we have a 16% chance that during some period the stock price will end up above $110.

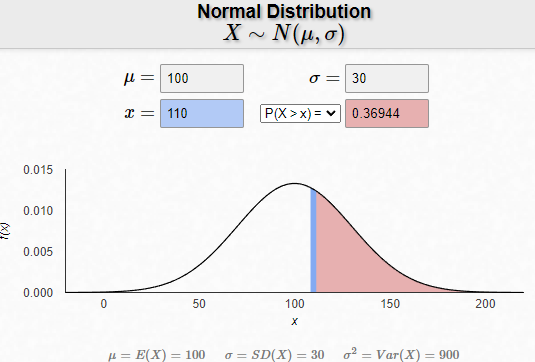

What happens if we increase the volatility?

So same option, same stock price, but higher standard deviation (aka higher volatility). Now there’s a 37% chance it will end up above $110 at some point. Dope.

But wait, isn’t there a bigger chance of it going to zero? Sure, but that’s not our problem because we own an option and not the actual asset so we don’t hold any price risk beyond the fee we already paid. The most we can ever lose is the $10 we already paid so we don’t care if it goes to zero temporarily as long we can still exercise our option when its “in the money”.

Wild.

Feel free to play with the distributions here more if you’d like

What’s intuition here?

If you can limit your downside risk exposure, volatility is your friend.

That’s cool I guess, but weird? I still want self-actualization!

We’re not wired to think that volatility equals good. In fact, it’s mostly the opposite.

In nature, volatility typically carries some amount of existential risk (tigers, loss of food source, other forever bad things). Volatility means you can’t be as certain on where you’re going to land with the outcomes. It means risk. It means maybe losing your shirt (or a lot more).

Except options provide a neat little hack to leverage volatility.

We saw this with the new outcome distribution with the call option. We capped our floor loss with the upfront fee we paid for the call option. So in a very real way we have established a fixed downside (-$1), but left open the possibility for unlimited upside.

So while this hack is neat and useful for markets, but it can also help us think about our lives and careers and when it is rational (or irrational) to make certain decisions.

It all comes down to this question.

Can you cap your downside risk?

If you can, then maximizing your career “value” means seeking out the highest possible volatility in your distribution of outcomes that’s humanly possible.

If you can’t, then you should probably focus on figuring out how to cap your downside risk to a level your circumstances can tolerate.

How do you do this? Read this for detailed exploration of reducing downside risk. The tl;dr is define your worst case scenario (be honest) and then work as hard as you can to create a backstop to get there (work at Google for a year or whatever). Then execute your high volatility plan!

In the framing from above, we’re looking to create some sort of career option that we can pay for upfront to remove the risk of total (or some unacceptable amount of) loss from our future prospects.

Obviously there’s a good amount of personality/emotional security/individual life style/lived experiences/preference hand waving going on from me here, but if you can honestly define what your life’s rational lower bound approximately is then you’re in a really powerful position (locus of control wise).

Now assuming you won’t have a mental breakdown if the bull case doesn’t work out (because remember you’re a rational actor who supposedly CAPPED their downside to the minimum point you’re truly comfortable with and if it’s truly capped you shouldn’t be freaking out if it happens) this is what I recommend for maximizing volatility in your career.

Ride the Lightning

But seriously. You have to pick things that give you the uh oh feeling to some degree. It’s ultimately dealer’s choice on the standard deviation you target, but you can’t potentially be one of the first ten employees at Amazon without working in a place like this. Volatility = uncertainty = risk (ok not technically, but it’s close enough).

Also, I guess it should also be said that there are choices that will skew distributions towards good (exercise, kale baths, etc) and bad (persistent drug use, punching your boss, etc) outcomes, but I’m going to also assume you won’t intentionally screw yourself up given that you’ve already read too much of this essay to back out now.

So in no particular normative order, here’s some choices you can make to induce good volatility into your career:

Join an earlier stage company in the same role in your current industry

Join a same stage company in the same role in your current industry

Join an earlier stage company in a different role in your current industry

Join a same stage company in a different role in your current industry

Join an earlier stage company in the same role in an industry with better macro tailwinds

Join a same stage company in the same role in an industry with better macro tailwinds

Join an earlier stage company in a different role in an industry with better macro tailwinds

Join a same stage company in a different role in an industry with better macro tailwinds

Start a startup

You might’ve noticed a pattern.

What I’m really trying to say is that while you don’t have to make a massive life change (although that is definitely going to induce the volatility you’re looking for), you do have to change something. It could be taking on more responsibility, asking for a promotion, working on a side hustle, starting a blog or other social media thing, or any of the thousand ways you can play the great online game we call life.

Growth begets capital and capital begets growth (the world is reflexive). Find problems with low cycle time solution iterations. Take a job with too much to do and not enough people to do it all (talk to me about this if you think crypto and fintech is cool). Go to organizations that generate a lot of serendipitous interactions. Hang out with optimists. Create things and ask people to critique them (terrifying).

And handling your downside risk first lets you credibly commit to doing this.

It’s scary (although rationally it shouldn’t be), but the math checks out. Or at least it checks out as much as intellectual career frameworks can hope to check out when trying to accurately price chaotic, multidimensional, individualized life utility functions.

So if you’re trying to get the most out of your career -

Cap your existential downside risk, pursue max volatility, repeat.

I hope this added value to your day.

Please share this with someone who might find this interesting!

If you have any thoughts or questions about this essay - Let’s Chat

To hear more from me, add me on Twitter or Farcaster,

and, of course, please subscribe to Wysr